How MLB could "flip the medium" (if they cared to think about doing so).

Web-based broadcasting of live events could transcend television, but most broadcasters prefer to look backward... and many other observations.

WARNING: This article is a plunge into a specifically geeky area of media studies. Before reading, you may want to look up Marshall McLuhan’s Tetrad, as well as the meaning of “Hot and Cool Media” and “Acoustic vs Visual Media”.

Here are a few video links that might help (or they might just create more questions.. that’s the McLuhan way, after all):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BNcy24WD4yk

—-a little note on this one: I don't mention the phrase “Hot and Cool Media” in this article, but the concept is still helpful. For the purposes of this article, McLuhan would classify baseball and cinema as hot media, but would classify football, basketball, and television as cool media. This is because “hot" media tends to force you to concentrate more intensely on specific scrutinized details (often in a linear fashion), whereas “cool” media tends to make you more involved by supplying a variety of disparate and vague details all at once. It may help to understand the delayed thesis of this article if one sees baseball and cinema as sharing something in their innate quality, while sports such as football and basketball are naturally better aligned with television.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eRnexsrlSdA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J3n65fa40JM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FWqOts9oq80

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T2W9Eii-Dsk

Many years ago, I created a video installation based on Marshall McLuhan’s Tetrad of Media Effects. I am not entirely sure that any living person who saw this sculpture in any of the galleries where I exhibited it had any idea what was going on. Even if they read my artist’s statement, they probably had no idea what the work of art was trying to say.

The Artist’s Statement: (excerpt)

“In this sculpture, each video clip has oblique signifiers (film melt, analog video interference, digital compression or pixelization, etc) edited into it to infer a battle between media or formats (film vs. video, analog vs. digital, etc). As living and mechanized cowboys shoot each other, one media format continually emerges to obsolesce, or assassinate the previous format.”

Many people told me that they loved the installation, but when I asked them, most people admitted that they didn’t understand what I was getting at in the artist’s statement. I can’t blame them since my signifiers in the video clips (designating certain media formats) normally lasted only about one or two seconds and seemed like a somewhat meaningless aesthetic choice. On top of this, few people understand McLuhan’s Tetrad when they are first exposed to it. The footage (from Michael Crichton’s original film of Westworld) had its own sense of spectacle, and so people enjoyed it for what it was, enjoyed the idea of TV sets shooting each other, and that was all they saw.

Would I revise this video project? Maybe if I were to exhibit it again. Personally, I HATE to go back and remake my projects. I am not good at getting back into the mindset I had when I first created a piece, and I would often rather look back at an artwork as an artifact of previous ideas, than a living, still-vital thing. Most art that I make is basically dead to me after the first exhibition. I am more interested in what I’ll make tomorrow.

Sports is sort of this way. Despite the significance of history, most fans don’t look back. They REMEMBER back. They talk about the legends of the past, they read about the legends of the past, and they watch films about those legends… but does anybody actually watch the old games? A youtube video clip titled “Furthest baseball ever hit” (it’s not actually) shows Barry Bonds hitting a dinger that disappears in the night sky. The video has over 9 million views, but (aside from very specific championship games) full recordings of sports events from previous seasons rarely break two hundred thousand views. We talk about sporting events from the past as though we can’t watch them now, but really, we don’t feel like reliving them. We prefer to live in the moment. When it comes to live events, we participate by watching live. When it’s over, we don’t feel compelled to view it, but can just watch a recap, or news of the event.

WHERE IS THIS GOING? You are probably wondering why I’m telling you these things. Marshal McLuhan? live video? sports? video art? obsolescence of media formats? What the hell? Let’s suspend our need for a thesis statement for just a bit, and I’ll lay out some more terrain before we reach any assumptions or conclusions…

I’d like to first start with Marshall McLuhan’s most well-known book, Understanding Media. Near the end of the book (in the parts nobody reads) McLuhan applies his premises that are introduced in the first chapters, to any kind of “media” that strikes his interest. Money, Housing, the Motorcar, The Wheel, Movies, Radio, Weapons, Games… nearly EVERYTHING is a “medium” in McLuhan’s view. The excerpt below appears under “Games”.

Mcluhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw Hill, 1964

Essentially, Baseball action occurs in a mode in which everything is very “one-thing-at-a-time”, but Football, which is less positionally fragmented contains a great deal of action that is happening all at once. Hunter S. Thompson described it this way…

…if sporting historians ever look back on all this and try to explain it, there will be no avoiding the argument that pro football’s meteoric success in the 1960’s was directly attributable to its early marriage with network TV and a huge, coast-to-coast audience of armchair fans who “grew up” — in terms of their personal relationship to The Game — with the idea that pro football was something that happened every Sunday on the tube. The notion of driving eight miles along a crowded freeway and then paying $3 to park the car in order to pay another $10 to watch the game from the vantage point of a damp redwood bench 55 rows above the 19-yard line in a crowd of noisy drunks was entirely repugnant to them.

And they were absolutely right. After ten years of trying it both ways — and especially after watching this last wretched Super Bowl game from a choice seat in the “press section” very high above the 50-yard line — I hope to christ I never again succumb to whatever kind of weakness or madness it is that causes a person to endure the incoherent hell that comes with going out to a cold and rainy stadium for three hours on a Sunday afternoon and trying to get involved with whatever seems to be happening down there on that far-below field.

At the Super Bowl I had the benefit of my usual game-day aids: powerful binoculars, a tiny portable radio for the blizzard of audio-details that nobody ever thinks to mention on TV, and a seat on the good left arm of my friend, Mr. Natural. … But even with all these aids and a seat on the 50-yard line, I would rather have stayed in my hotel room and watched the goddamn thing on TV.

Thompson, Hunter S. “Fear and Loathing at the Super Bowl”. Rolling Stone, 28 Feb 1974

Now, if I may build an argument on top of Thompson’s rant:

Baseball is easy to follow in the stadium because the action is spaced out into a sort of assembly-line of events. The ball is pitched, if it is hit, then the closest player on the field (who generally only covers his own designated patch of turf) tries to catch the ball and send it to the base that the batter (or previous batter) is about to arrive at. Each man covers his own space and the ball is sent from one person to tlhe next. It’s all one-at-a-time. By contrast, football is a wild mess of multiple players trying to mob-crush anyone with the ball. Baseball is spaced out and easy to watch from the stands, but football is a tangled fight that often requires a zoomed in camera to decipher.

Marshall McLuhan was not the only person to observe that television had a technological bias towards football and against baseball. For decades now, MLB viewership on television has slowly dwindled, and the NFL (despite their inept handling of public relations, despite concussion studies, despite their overt racism, etc etc.. do I really need to list it all?) essentially owns television and cable networks who absolutely need grand-scale live events to compete with internet-based on demand video.

This state of affairs appears very constant. TV and the NFL seem to need each other, while the MLB continues to slowly dwindle in popularity. This has been happening for a lifetime. But, let’s go back to the idea of McLuhan’s Tetrad (the strange starting point of this article) to think about what the future holds.

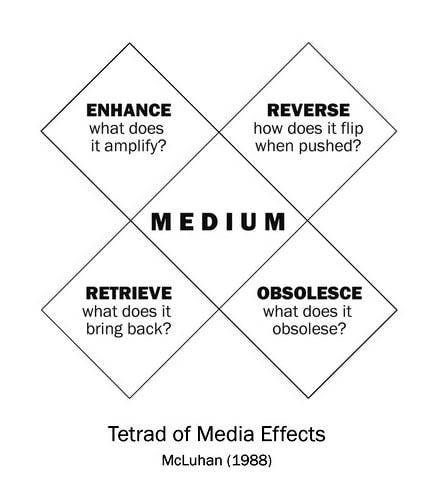

The Tetrad is a field of four conditions that accompany any medium. What does a medium enhance, reverse, retrieve, or obsolesce about our culture?

I could write pages and pages about how this chart works, but it’s much easier to understand by looking at a few examples. Let’s start with something from way back…

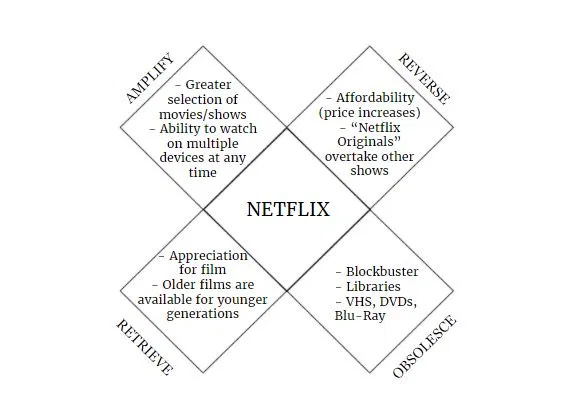

Now, let’s pick some more recent/relevant artifacts…

…as one can see here, each medium pushes culture in different directions when it increases in popularity to become a dominant form.

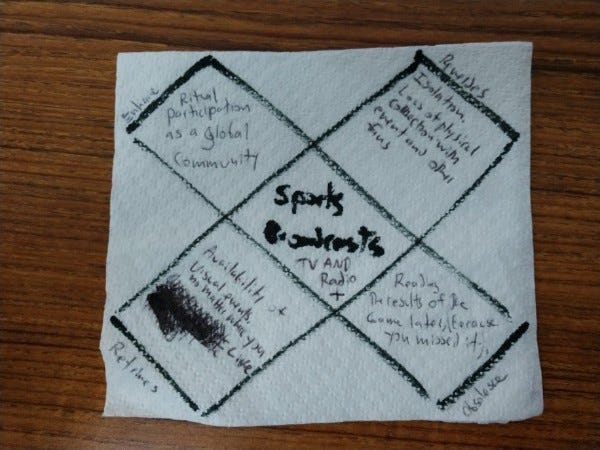

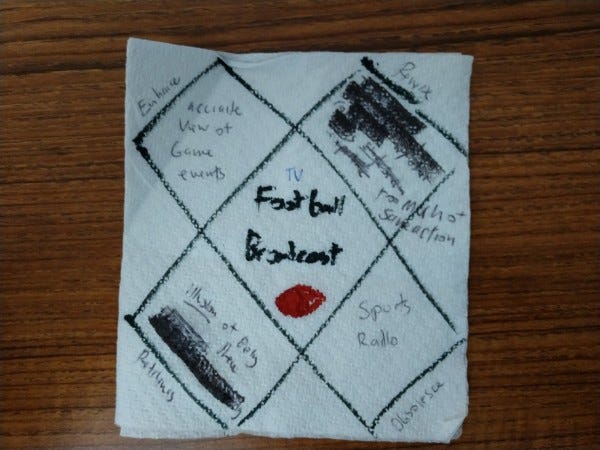

SO, now I would like to approach our long-awaited thesis concept with some messy hand-drawn tetrads of my own (done a few weeks ago on diner napkins… the ultimate concept catcher). I feel there is something to be gained in the exegesis of concepts from hastily scribbled notes, as it forces one (me, in this case) to dig back into his own brain mechanics to examine the original impulse and the root of the idea… or something.

ABOVE: Sports broadcasts, in general (Mostly TV and radio), enhance ritual participation by magnifying it. Instead of just a local event, the ritual is participated in globally in real-time. The live events (and associated recaps) obsolesce the need for printed results. While fans TODAY check prior “print” data online (another tetrad in it’s own right), the sports section in the paper is more relevant when it tells the stories not seen on the screen. These broadcasts also retrieve the visual experience of sporting events (because you can now see the games you previously couldn’t attend) while reversing the effects of seeing the game in person (assuming you could have gone) by isolating you from the crowd. You now participate without being there. You are aware of the crowd and the game, but they are not (specifically) aware of you. You are united to the event in your own head, and so are the other global members of the crowd who are watching the game from a distance. The thousands/millions of you might possibly interact somewhat online during the game, but each crowd member is mostly siloed. You have gained possibly millions of new audience members that you share the game with, and yet the quality of your interaction is diminished.

ABOVE: Football and basketball are both less linear than baseball and so they both look to live broadcasts to reveal the actions of the game more accurately. In a stadium, it’s not easy to see what’s happening when many players mob the ball and each other, so these two forms completely obsolesce sports radio (just because you can SEE the event at all), but also accidentally (partially) obsolesce live game attendance by giving you accurate views of the event in real time. The need for close-up camera angles sets these sports apart from baseball because in football/basketball you literally need a close-up to see who has the ball at certain key moments. Important details can be seen on television in a way that puts both the radio and the cheap seats at the stadium to shame. Both of these broadcasts also retrieve participation in the game itself for people who couldn’t see it otherwise, but they also currently threaten to reverse the game into meaninglessness making all games available all the time and offering a similar pattern of broadcasting techniques.. Over, and over, and over.

Of course, if you are a fan of the Falcons, you find it valuable that you can watch any/every Falcons game from nearly anywhere in the world, but the flip-side of this bounty is that when all games are filmed using the same “best-practices”, so that you can see the action from the best angle at all times, we now find ourselves with a mind-numbing stream of games that represent all sports in a very similar package. One “first-world problem” is that one could argue that games were more special when you could not watch them all, all the time, but I’d like to offer a different way of looking at the reversal of this media form, and this is where the broadcasting of baseball comes in….

ABOVE: Generally speaking, baseball broadcasts, including MLB, MILB, college ball, Little League championships, etc, all offer degrees of the same broadcasting practices (though production value obviously varies). In terms of camera work and editing, however, they miss an opportunity to do something that cannot be done with many other sports such as football and basketball. Like the other two sports discussed here, televised baseball utilizes one or more (usually more) “roaming” cameras that follow the action of the game by panning, tilting and zooming across the field, while several other cameras maintain a somewhat fixed position. Typically there are eight cameras used, in total. This way, the action can always be covered and live edited together with “establishing shots” or more fixed shots of the field and crowd.

Looking at the baseball napkin, we see only two differences between it and the basketball/football napkins. One is that, while baseball video broadcast obsolesces radio, it does not do it to the same extent that video of basketball/football do. This is, again, because of the “assembly line” nature of baseball. Text and speech are linear and so is baseball. You can describe the events of a baseball game one action at a time, but you can’t describe all the elements of the football field melee in a linear fashion (in real time) without missing something. Baseball is still enjoyable on the radio as well as TV, while, In the opinion of this author, football and basketball on the radio are a mind-numbing hot mess*.

*Though definitely NOT “hot” in McLuhan speak as referenced in the links at the top of this article.

The second difference on the baseball napkin is that when the form reverses, the slower, linear event of baseball starts to seem boring on television, and does not show the audience very much that a radio broadcast or a live viewing would not reveal. This, I would argue is THE reason that televised baseball cannot compete with basketball and football.

see here…

Notice that, even though this is excellent baseball (Max Scherzer exhibiting prime pitching skill against three very valid opponents, it seems like very little is happening, and we spend most of the time looking at replays. To a hardcore baseball fan, this is very compelling, but to everyone else, it’s slow and hard to appreciate.

NOW, let's imagine baseball as cinema. I mean, instead of baseball as TV. Before writing this, I watched scenes from about 10 different baseball movies looking for the ideal sequence to show here as a contrast to the Scherzer video above. If you've ever seen a baseball movie, I'm sure that you can imagine the difference. Imagine the famous home run scene from the The Natural… but, the thing here is that that scene incorporates story elements that nobody would know about during a regular baseball game. So compelling as it is, it's not really a good comparison. So in the place of such a movie that combines the personal story elements of the characters with the elements of the public game, I thought I would share this famous scene from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

In this scene, we see all of the crucial information of the confrontation displayed, but we also see a dazzling variety of unique detail shots. The scene is, of course, famous as an example of really excellent extreme close-ups.

Instead of the typical eight cameras, imagine the variety of establishing shots and detail shots and action shots that one could get if there were, let's say, 100 cameras.

Most viewers never think about the camera operators who bring baseball to our home televisions, but they do their job with incredible skill (there is an excellent article about this here). I propose that baseball, and ONLY baseball (as opposed to other popular sports) could be less like television, and more like cinema if these camera operators and live editors had a much larger variety of images at their disposal to work from. Even if the majority of the “100 cameras” had fixed ranges and were controlled robotically by algorithms, (though you would still need many camera operators), the variety of images could give a skilled production team a much more visually powerful end product. This level of visual mastery is what differentiates cinema from television. Television (especially live television) is typically not as visually oriented as cinema. Normally, this is because the television product is produced on a tighter deadline and films are visually planned out over a greater time span from the first story board to the final editor's touches.

Live events typically don't give an editor the luxury of time, but an editor who produces 162 games a year (the number of games in an MLB season) should be practiced enough to pull images together in a clever way. In addition to being a “slow sport”, a baseball game always follows a fairly predictable path. Each team will have the plate until three people strike out. Nobody is going to steal the ball and reverse possession. Nobody is going to run the bases backwards. It might take a very carefully constructed team of editors, but if the pacing of a baseball game becomes a natural extension of an editing team’s natural psyche, a baseball game could definitely become more of a cinematic visual form and less of a typical televised video form.

McLuhan stated that television was really, at its heart, an acoustic medium, unlike film which is a visual medium. Think about it. You have the game on. You're doing dishes while watching it. You're snacking. You're talking to your friends. You're going in and out of the room and catching up on the game when you come back. This is how we watch television. By contrast, if a really good movie is on, you can be glued to your seat. Imagine watching a game that visually catches nuances from various players while we wait for the action to unfold. We are used to seeing close-ups of the pitcher and the batter but we rarely see much else. What if (like the scene above from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly), we could see a panorama of visuals that heighten the intensity of each hit or each strike? The slower pace of baseball and the spaced out nature of its assembly line of events is the thing that makes this possible. The very list of things that make many people think baseball is a boring sport are the things that could allow a production crew to find the best out of 100 camera angles, and then edit them together in a creative fashion, even live and on the spot. I would send this message to Major League baseball. I would send it to all the marketing people, to Rob Manfred the current commissioner of baseball, to all the cable executives, and all the MLB producers, though I don't expect they would read it. But if they chose to adopt these tactics, they could absolutely flip baseball into a cinematic medium and flip their position in the marketplace and become, again, the most watched and most compelling of American sports.

In summation, all of this theory supports just two major changes:

-At least 10 times the cameras.

-On the spot cinematic editing that focuses on intensifying the narrative rather than just simply showing the events of the game.

The technology exists to do this. Television becomes more of a cinematic experience everyday (just compare mid-century sitcoms and teleplays with more contemporary series such as Stranger Things, Breaking Bad, The Mandolorian, Squid Game, etcetera. Baseball is the one sport that could most easily adopt this media transformation and create a type of live televised experience that would put it, visually, head and shoulders above any other sports production on television.

I'll end with this prediction:

Either Major League Baseball will end up doing something like what I suggest here (they will figure it out on their own. I don't think my writing this will change anything), or it will die a slow death over the coming decades and become a sport that only a very small handful of Americans still watch.

I guess I'm going to have to read this article again in 30 years and see where we are.

-Tyrone Davies

i agree with your fundamental argument but disagree on some of the details